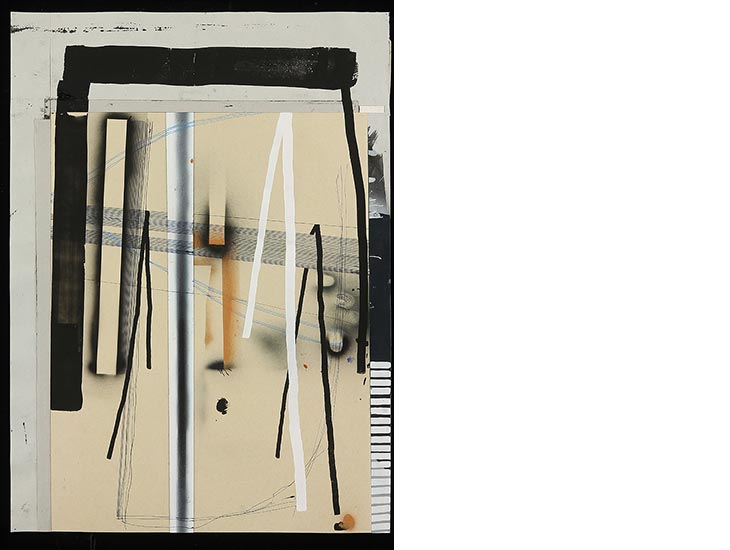

If some artists’ studios are factories, efficient and methodical, and some are gardens, cultivated and seasonal, the model for Shaun O’Dell’s studio is more primordial. Images and themes evolve, thrive, and break down, to be reintegrated into another generation. O’Dell might cut a painting apart and splice the ribbons into a new composition, or use one surface to print off another. Thin lines of gouache, loose airbrushed lattices, and veins of smeared color overlay and offset each other in periodic cycles of organization and disintegration. Shared ancestry links the individual pieces; a color, pattern or mark just visible in one painting might dominate the surface of another. For all their changes, though, the abstractions in this exhibition aren’t the conclusions of O’Dell’s process, because the process doesn’t end. They’re moments of equilibrium plucked from a perpetual state of adaptation.

This studio ecosystem is O’Dell’s alternative to an American ideology he sees as disastrously overreaching. A utopian society will sacrifice the present for the sake of a perfect future, and the history of the United States is littered with those compromises. People, animals, land and resources have been exploited and destroyed in service of a social and economic ideal that might never arrive.

In place of that unsustainable ambition O’Dell posits a provisional, imperfect union. No future or past state enjoys any special reverence. If his practice points to an ideal it isn’t any single product or place, but a flux that matches the unsentimental momentum of the natural world.

Though not visually similar to his paintings, O’Dell’s prints on marble extend his thinking on time, specifically time as a corrective to the distortions of history. Time and history are often viewed interchangeably, but where time is a physical fact, history is a superimposed narrative with its own biases and sensibilities. History as it’s told has high points and low points, golden ages and dark ages, purpose and lessons. Time by itself doesn’t admit those categories, and neither does O’Dell. He scanned photographs of statuary from Andrew Stewart’s compendium of Greek sculpture, cropped the images, and printed the results on marble slabs. Every intervening stage is a deviation from the sculptures’ original, “perfect” state: millennia of wars and neglect left them disfigured, photography compressed them into a new medium, scanning abbreviated them further, and cropping detached them even from their academic context. But to describe the consequent prints as adulterated or ruined supposes some ideal version insulated from the flow of time, and diminishes the immediate pleasure to be taken from the newly abstracted forms, or the veins of the marble slabs blending with the marble of the printed images. As with his paintings, O’Dell is sensitive to what these objects were, and what they might be, but not at the expense of what they are.

The prints on marble share the South Gallery with O’Dell’s sculptures, a collection of evocative but ambiguous shapes encrusted in a granular off-white patina. Some of the sculptures hint at their origins – the crooks of one are distinctly branch-like – but all are in a transitional stage, ensconced in a common exterior that largely blots out what they once were. It isn’t even possible to tell whether O’Dell started with found objects or built the forms himself, and the uncertainty dispels any notion of a stable identity. The sculptures might be clutter from O’Dell’s studio floor, formal experiments, or fragments of an imagined shipwreck, but more than anything else they’re an inventory of objects developing into a register of time.

In a final turn, O’Dell brings the audience itself into the endless churn of production and reproduction. By linking a video recorder to a projector and pointing them both at the same gallery wall, he catches passers-by in a feedback loop, an infinitely regressing projected image that deteriorates as it recedes. The digital decay, together with the assortment of losses, accumulations, repetitions and distortions in evidence throughout the exhibition, mirrors the forces O’Dell sees at work in both the environment and the built world. And ultimately, the transformations generated by a single artist in his studio aren’t qualitatively different than those caused by accidents, migrations, wars or erosion. They’re only distinctions of scale.

—Josh Bernstein